Opinions

Smart lighting: enabling smart cities beyond illuminationSponsored by Paradox Engineering

How AI and biometrics are shaping next-generation mobility paymentsSponsored by ST Engineering

Sharing and collaborating on green innovation in Stockholm

Carl Piva, chair of Stockholm Green Innovation District, illustrates the role that the organisation is playing in pushing public and private sector sustainability efforts forward in Sweden’s capital and beyond.

SmartCitiesWorld (SCW): Tell us about your role as chair of the Stockholm Green Innovation District, and what the organisation is trying to achieve.

Carl Piva (CP): My day job is as the CEO of the Swedish Internet Foundation, an organisation similar to Nominet in the UK, but with a slightly broader scope. I also hold the position of chairman of the Stockholm Green Innovation District, an initiative founded by a former finance minister Allan Larsson after he moved to a newly-built district in Stockholm designed using circular principles.

Over the years, the district has become a popular destination for visitors from around the world, attracting numerous politicians and urban leaders who are seeking inspiration and knowledge to implement sustainable practices in their own regions.

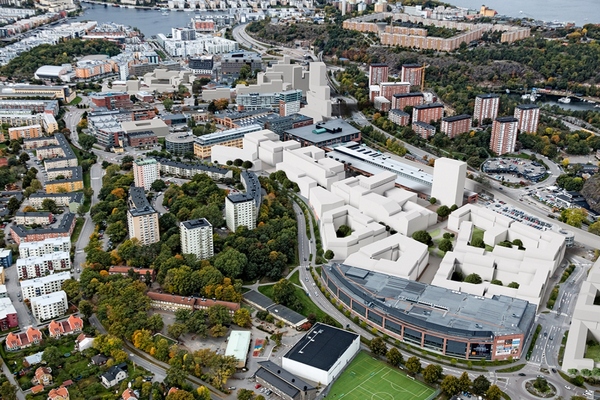

The Stockholm Green Innovation District’s primary goal is to re-imagine how a city district, recently built to be circular and twice as good as anything else in the world, could be further improved using civic engagement as a crucial tool. The district encompasses specific geographic areas in Stockholm, including newly built zones along a commuter train line.

While municipal governments control and must reduce CO2 emissions, it is helpful to recognise that most of the total reduction required falls on businesses, individuals and communities to bring about

One of the district’s other key aspects is fostering collaboration between different types of organisations and acting as a think-tank for sustainable development. We also look to establish cooperation among all the green capital cities in Europe, building on Stockholm’s position as the most innovative region in the European Union. We plan to invite other cities, including Bristol in the UK, to join us in a broader collaboration focused on innovation and sustainability.

SCW: What kind of initiatives is the Innovation District involved in to support decarbonisation within Stockholm?

CP: While municipal governments control and must reduce CO2 emissions, it is helpful to recognise that most of the total reduction required falls on businesses, individuals and communities to bring about. That means that our focus is on addressing those other aspects, aiming to drive change through civic engagement.

In my previous experience in the smart city arena, with TM Forum, I noticed a lack of involvement from citizens despite various sustainability efforts. Simply put, if you don’t present a compelling case to citizens, you won’t get their active involvement. To make

this happen, the district takes a more targeted approach to engagement. For example, engaging with housing cooperatives within the district, we demonstrated how sustainable practices could lead to cost-savings on energy bills. This approach garnered interest from cooperative boards as they saw the benefits of energy efficiency for their buildings, not just from a sustainability perspective but from a cost perspective. As a board member of a housing cooperative, you have a fiduciary responsibility, and voilá, the compelling case is made.

By focusing on the common interest of cost-savings rather than solely on climate change, we managed to involve a broad spectrum of people who might not have otherwise been interested in sustainable development. Some of these housing cooperatives achieved more than 50 per cent reductions in energy costs – up to 80 per cent in some cases – through collaborative energy-sharing and implementation of energy conservation solutions.

SCW: The Innovation District sounds like it’s quite close knit – does it feel that way, and that everyone is on board pulling towards a common goal?

CP: You have to identify your local champions and turn them into local heroes, as engagement turns out to be very local. We do have a strong belief in the power of testbeds, which gives us unique opportunities to involve companies with sustainable innovations and embed them within our district to test and prove their solutions. Obviously, this not only benefits the companies themselves but also makes the district itself more appealing, attracting more top talent that’s eager to explore and implement new ideas. When the desired outcome has been proven, others are more likely to deploy the same solution, not having to be persuaded.

Having such a wide array of stakeholders involved means we can connect the dots efficiently between demand and supply, and plan ahead for a cohesive and sustainable future

Global players like Siemens have found our district an exciting testing ground for their sustainable initiatives, but we also actively welcome smaller, lesser-known companies with innovative ideas, giving them the chance to trial their innovations.

The district currently has around 80 active participating companies. It’s a diverse group which includes academic institutions, landlords, building companies, and a slew of technology companies. Some of these organisations actually own significant portions of the land within the district, which allows us to collaborate even more closely in shaping the future development and ensuring that all aspects align with our sustainability goals.

Having such a wide array of stakeholders involved means we can connect the dots efficiently between demand and supply, and plan ahead for a cohesive and sustainable future. The district benefits from the expertise and resources brought in by the companies, while the companies themselves gain from the local connections and collaborations that are a result of being part of the district.

SCW: To what extent does a testbed approach within the Innovation District support start-ups and scale-ups in gaining wider exposure for their work and tech?

CP: The testbed approach has proven to be beneficial for start-ups and scale-ups looking to gain wider exposure. That was in place well before I became chair, and it has been instrumental in propelling companies with a sustainability edge into the limelight.

These innovative companies are able to receive significant visibility and recognition through the various collaborations and initiatives that being part of the district allows. Being part of the testbed ecosystem also allows them to showcase their sustainable solutions to a global audience, as we attract visitors from all around the world.

One excellent example of this is the recent project launched by Atrium Ljungberg, a sustainable urban development firm. They have launched a “Wood City” concept, which is the largest new build for sustainable development using wood

in the world. Wood City spans 250,000m2 in Sickla, which is part of our innovation district, and includes 7,000 new workspaces and 2,000 new housing estates.

Hosting innovative projects and forward-thinking companies like this within the district, we not only provide them with a platform to showcase their solutions but also offer them the opportunity to tap into a larger market. The global exposure they get here can lead to new partnerships, collaborations, and business opportunities that would be harder to access otherwise.

Another significant step forward in our sustainability efforts is engaging in the development of a digital twin for the district and its testbeds. The digital twin will be a powerful tool, allowing us to overlay the various types of savings and efficiencies that sustainable innovations are able to contribute. It will help to simulate different scenarios and explore what-if situations, which is really valuable because we want to understand the potential impact of deploying these solutions in other parts of our district and beyond.

We are also in the early stages of establishing an Urban Twin Transition Centre. This centre will be dedicated to empowering cities within the Viable Cities program to achieve their sustainability goals. There are 23 cities in Sweden and 40 per cent of our population resides within them, so the goal is to create a competency centre that provides science-based practical guidance on how to implement sustainability plans more effectively.

The ultimate vision is to empower smaller cities and provide to them the necessary tools and knowledge to affect positive change within their communities

As part of the Viable Cities initiative, there are also individual climate plans signed with those 23 cities. While these cities have defined their vision, they often face challenges when it comes to turning targets into actionable plans. The Urban Twin Transition Centre aims to bridge this gap by showcasing real, accessible solutions that can drive positive change within these cities. We aim to gather the best existing sustainable solutions from various sources, not just within our district but globally, to highlight their effectiveness.

The ultimate vision is to empower smaller cities and provide to them the necessary tools and knowledge to affect positive change within their communities. We understand the challenges faced by these cities and believe that providing guidance and access to working solutions will be instrumental in accelerating the transition to sustainable practices.

SCW: How active and how close is the collaboration between the Innovation District and the city itself?

CP: We have a strong connection with Stockholm City Hall, which has recently appointed its new climate czar to lead the city’s efforts in becoming climate positive by 2030. The city has taken several actions, with a next major milestone being the reduction of around 800,000 tonnes of CO2e annually, using carbon capture and storage.

However, there are still further steps the city can take, and that’s where our collaboration comes into play. We aim to provide a blueprint for other districts within Stockholm and the broader Viable Cities programme, enabling them to replicate our civic engagement model. In the Stockholm Green Innovation District, we have a dedicated team of individuals working full-time to drive sustainability initiatives and engage with the local community. This model is self-funding and has proven effective in inspiring positive change.

We are working to export this model to other progressive districts in the city and beyond. As the city addresses its own problems, initiatives like ours will prove to be vital to address private consumption and reduce energy consumption.

Cities now realise they share the same set of challenges, but the supply chain revolution hasn’t fully materialised as yet

To make progress and gain the trust of people who are unfamiliar with our work, you must first earn their trust. Initially, we focus on providing support and solutions around, for example, energy efficiency and electric vehicle charging to demonstrate tangible benefits. Once we have gained people’s permission and trust, we can move forward and delve into more complex challenges, including behavioural changes necessary to achieve lasting sustainability goals.

Ultimately, our ambition is to expand from achieving “hard savings” to addressing “softer” areas that require significant behavioural changes, like encouraging different modes of transportation, altering consumption patterns, and promoting sustainable lifestyles.

SCW: How could the approach the innovation district has taken to collaboration and engagement be replicated for other cities?

CP: One of the key realisations we had in our journey is that while each city may initially perceive itself as unique, there are common challenges and requirements shared among them. It’s similar to what we saw in the telecoms industry during the 1990s; companies like BT, Telia, Telenor, and Deutsche Telekom all believed they were unique and handled customer needs in their own proprietary ways. However, with the deregulation of the telecoms market, various vendors emerged, offering solutions to the same problems in many places, leading to a supply chain revolution. One company could serve the same need for many telecos.

Similarly, I think cities are at the cusp of experiencing a similar transformation. Cities now realise they share the same set of challenges, but the supply chain revolution hasn’t fully materialised as yet.

This recognition opens up great possibilities for cities to collaborate and learn from each other’s experiences. Rather than each city independently finding solutions to a common problem, they can tap into a collective knowledge base and benefit from shared expertise.

In essence, the Stockholm Green Innovation District’s success in fostering collaboration and civic engagement provides a blueprint for other cities to follow. This kind of collective effort will create a network of cities working together to implement proven solutions, effectively addressing common issues, and making a significant impact on a global scale.

To find out more, go to Stockholm Green Innovation District.

Why not try these links to see what our SmartCitiesWorld AI can tell you.

(Please note this is an experimental service)

How does civic engagement drive sustainability in Stockholm Green Innovation District?What role do testbeds play in supporting green start-ups and scale-ups?How can digital twins enhance urban sustainability planning and impact assessment?In what ways does collaboration between public and private sectors reduce CO2 emissions?How can Stockholm’s model be adapted for sustainability in smaller cities?